National Institutes of Health issued the following announcement on April 16.

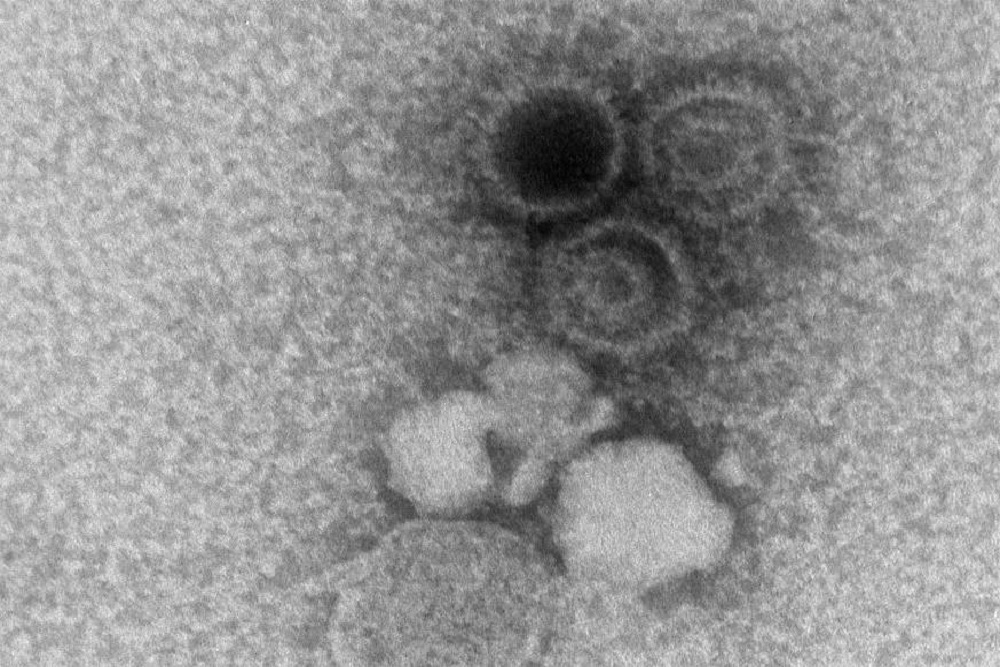

Infection with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), the cause of infectious mononucleosis, has been associated with subsequent development of systemic lupus erythematosus and other chronic autoimmune illnesses, but the mechanisms behind this association have been unclear.

Now, a novel computational method shows that a viral protein found in EBV-infected human cells may activate genes associated with increased risk for autoimmunity. Scientists supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases report their findings today in Nature Genetics.

“Many cases of autoimmune illness are difficult to treat and can result in debilitating symptoms. Studies like this are allowing us to untangle environmental and genetic factors that may cause the body’s immune system to attack its own tissues,” said NIAID Director Anthony S. Fauci, M.D. “A better understanding of the complex causes of autoimmunity promises to lead to better treatment and prevention options.”

EBV infection is nearly ubiquitous in the human population worldwide. Most people acquire EBV in early childhood, experience no symptoms or only a brief, mild cold-like illness, and remain infected throughout their lives while remaining asymptomatic. When infection first occurs in adolescence or young adulthood, EBV can lead to a syndrome of infectious mononucleosis characterized by prolonged fever, sore throat, swollen lymph nodes and fatigue. This syndrome, also known as “mono” or the “kissing disease,” generally resolves with rest and only rarely causes serious complications.

When EBV infects human immune cells, a protein produced by the virus — EBNA2 — recruits human proteins called transcription factors to bind to regions of both the EBV genome and the cell’s own genome. Together, EBNA2 and the human transcription factors change the expression of neighboring viral genes.

In the current study, the researchers found that EBNA2 and its related transcription factors activate some of the human genes associated with the risk for lupus and several other autoimmune diseases, including multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, type 1 diabetes, juvenile idiopathic arthritis and celiac disease.

Previous studies suggested that EBV infection may result in autoimmune diseases, particularly lupus. In the current work, researchers led by John B. Harley, M.D., Ph.D., director of the Center for Autoimmune Genomics and Etiology (CAGE) at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, with his colleagues Matthew T. Weirauch, Ph.D., and Leah C. Kottyan, Ph.D., also of CAGE, wondered whether genetic analysis could further explain the relationship between EBV infection and lupus. Their team developed a new computational and biochemical technique known as the Regulatory Element Locus Intersection algorithm, or RELI. Sifting through and comparing a large collection of genetic and protein data from healthy individuals and those with autoimmune diseases, the team used RELI to identify regulatory regions in genes associated with the risk of developing lupus that also bound EBNA2 and its related transcription factors.

“We were surprised to see that nearly half of the locations on the human genome known to contribute to lupus risk were also binding sites for EBNA2,” said Dr. Harley. “These findings suggest that EBV infection in cells can actually drive the activation of these genes and contribute to an individual’s risk of developing the disease.”

In follow-up analyses, the investigators used RELI to probe regulatory genes associated with other autoimmune diseases and found that EBNA2 bound to genes associated with the risk for multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, type 1 diabetes, juvenile idiopathic arthritis and celiac disease.

“Because EBV is most often encountered in early childhood, avoiding infection is practically impossible,” said Daniel Rotrosen, M.D., director of the Division of Allergy, Immunology and Transplantation at NIAID. “However, now that we understand how EBV infection may contribute to autoimmune diseases in some people, researchers may be able to develop therapies that interrupt or reverse this process.”

Researchers note that EBV infection is not the only factor that contributes to the development of the seven autoimmune conditions discussed in the paper. Many of the regulatory genes that contribute to lupus and other autoimmune disorders did not interact with EBNA2, and some individuals with activated regulatory genes associated with disease risk do not develop disease.

NIAID conducts and supports research — at NIH, throughout the United States, and worldwide — to study the causes of infectious and immune-mediated diseases, and to develop better means of preventing, diagnosing and treating these illnesses. News releases, fact sheets and other NIAID-related materials are available on the NIAID website.

Original source can be found here.