A drug used to suppress seizures in a genetic zebrafish model could hold hope for some epileptic children resistant to known anti-epileptic drugs, the National Institutes of Health reported recently.

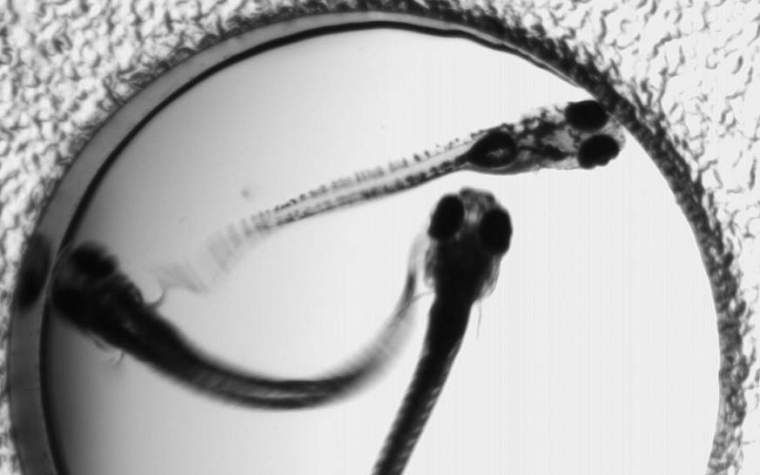

The report followed a study, published in the journal Brain, that focused on children suffering from Dravet syndrome, a severe form of pediatric epilepsy. The researchers first introduced a genetic mutation into zebrafish to cause epilepsy, which was followed by the administration of the drug lorcaserin, which appeared to suppress seizure activity.

The researchers then administered the same drug to five children with Dravet syndrome. After initial administration, all of the children showed a decrease in seizure activity. And although seizure activity had increased three months later, it did so less frequently, and none of the children suffered any severe side effects.

“This is the first time that scientists have taken a potential therapy discovered in a fish model directly into people in a clinical trial,” Vicky Whittemore, program director at the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), said. “These findings suggest that it may be possible to treat neurological disorders caused by genetic mutations through an efficient and precision medicine-style approach.”

The NINDS, part of the NIH, supported the study, which was undertaken by Scott Baraban, a professor of neurological surgery at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF); postdoctoral fellow Aliesha Griffin; and colleagues.

Dravet syndrome is characterized by developmental delays and frequent seizures that so far have proven resistant to epilepsy drugs.

Baraban and his colleagues are now studying the potential role of a second drug, clemizole, in combination with lorcaserin, for trials focusing on interaction with the human serotonin system.